- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Students

- Andean Food Series: The sapote

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

What is an anaco, a garment found in the funerary bundle of the Lady of Cao and in the Lambayeque funerary bundles? ...

Inauguration of the 2025 Tourism Panel Discussions in Magdalena de Cao ...

To receive new news.

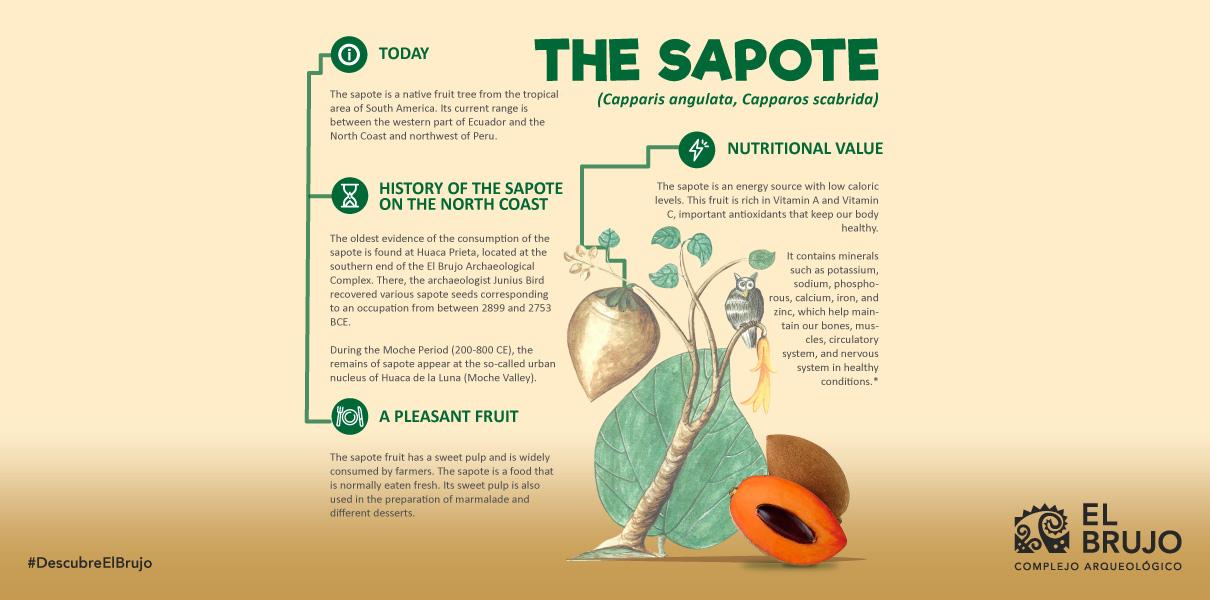

Por: Jose Ismael Alva

The sapote (Capparis angulata, Capparos scabrida) is a native fruit tree from the tropical area of South America. Its current range is from the western part of Ecuador to the North Coast and northwest of Peru. In the regions of Tumbes, Piura, Lambayeque, and La Libertad, the sapote can grow at altitudes of up to 2000 meters above sea level (Fernández and Rodríguez 2007, pg. 97; León 2013, pg. 278). We will now review the history of this fruit and its nutritional properties.

Biological properties of the sapote

The sapote belongs to the group of xerophytic plants, meaning those that have evolved to store water and thus survive in ecosystems with little rain. In desert zones, they capture moisture from groundwater (Fernández and Rodríguez 2007, pg. 97; H. Gonzales et al. 2015, pg. 23-24).

The plant’s growth can be variable; however, an average growth of 3 meters in 10 years has been measured, attaining a final height of 10 meters. Meanwhile, only 60% of sapote plants produce fruits, with this process occurring between September and February. (E. Gonzales et al. 2013, pg. 8; H. Gonzales et al. 2015, pg. 24-25).

History of the sapote on the North Coast

The earliest evidence for the consumption of sapote is found at Huaca Prieta, located at the southern end of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex. There, the archaeologist Junius Bird recovered sapote seeds corresponding to an occupation from between 2899 and 2753 BCE (León 2013, pg. 279). Later on, the excavations of Tom Dillehay and Duccio Bonavia recovered remains of the fruit in association with the final phase of occupation at the pre-Ceramic building, dating to the start of the second millennium BCE (Dillehay 2017, Ch. 10).

During the Moche period (200-800 CE), remains of the sapote appear at the so-called urban nucleus of Huaca de la Luna (Moche Valley), in spaces used for the preparation of food and artisanal activity (Vásquez and Rosales 2006, pg. 292).

Centuries later, the Lambayeque towns (900-1375 CE) in the valley of the same name had a diverse diet of marine resources, land animals, and plants. In the latter group, the sapote was one of the ten most consumed botanical products (Klaus and Tam 2010, pg. 596).

During the Viceroyalty in Peru, the Indigenous communities that resided in the town of Magdalena de Cao at the El Brujo Archaeological Complex largely maintained their preferences for native fruits. The research of Jeffrey Quilter on the remains of this Spanish reducción revealed the continuity of consumption of sapote during Colonial times (Quilter 2020, pg. 86).

2.jpg) Depiction of the leaves, flower, and fruit of the sapote. Drawing from the 18th century published by Bishop Baltasar Martínez Compañón (Martínez Compañón 1998, Fig. 29).

Depiction of the leaves, flower, and fruit of the sapote. Drawing from the 18th century published by Bishop Baltasar Martínez Compañón (Martínez Compañón 1998, Fig. 29).

A pleasant fruit

The fruit of the sapote has a sweet pulp and is currently widely consumed by farmers. It has also been reported as the preferred food of coastal birds and foxes. These animals contribute to the dispersal of its seeds and promote the germination of sapote plants in new places (H. Gonzales et al. 2015, pg. 25). The sapote is a food that is mainly eaten fresh. Its sweet pulp is also used in the preparation of marmalade and different desserts.

There have been recent efforts to industrialize the reddish gum produced by the sapote tree. This gum, whose raw odor is similar to that of sugar, has been tested with positive results in the chocolate and marshmallow industries (E. Gonzales et al. 2013, pg. 15-16).

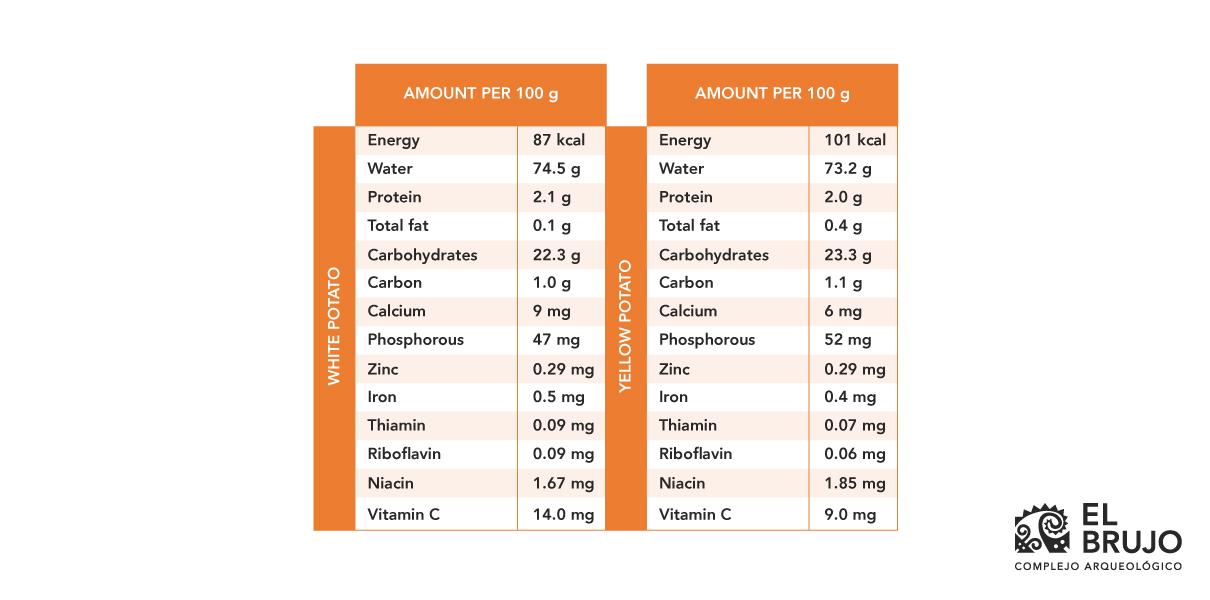

Nutritional value of sapote

The sapote is a source of energy with low caloric levels. It also has a high water content that helps us stay hydrated. This fruit is rich in Vitamin A and Vitamin C, which are important antioxidants that keep our body healthy.

This tropical fruit also contains B-group vitamins, among which its concentrations of Vitamin B3 are notable, which is linked to the correct functioning of the digestive system, the skin, and the nervous system.

Finally, the sapote contains minerals such as potassium, sodium, phosphorous, calcium, iron, and zinc, which contribute to maintaining the bones, muscles, circulatory system, and nervous system in healthy conditions.

Depiction of the leaves, flower, and fruit of the sapote. Drawing from the 18th century published by Bishop Baltasar Martínez Compañón (Martínez Compañón 1998, Fig. 29).

References

Dillehay, T. D. (Ed.). (2017). Where the Land Meets the Sea. Fourteen Millennia of Human History at Huaca Prieta, Peru. Texas University Press.

Fernández, A., & Rodríguez, E. (2007). Etnobotánica del Perú Pre-Hispáno (Herbarium Truxillense). Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Gonzales, E., Begazo, K., Guzmán, D., Chire, G., & Ascencios, D. (2013). El árbol de sapote (Capparis scabrida) como recurso forestal. Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina.

Gonzales, H., Llacsahuanga, D., & Valdiviezo, N. (2015). Compendio de trabajos de investigación realizados en el Subproyecto 1: Goma de sapote (Programa de Cooperación VLIR/UOS-UNALM, Vol. 1).

Klaus, H., & Tam, M. (2010). Oral health and the postcontact adaptive transition: A contextual reconstruction of diet in Mórrope, Peru. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 141, 594-609.

León, E. (2013). 14,000 años de alimentación en el Perú. Universidad de San Martín de Porres.

Martínez Compañón, B. (1998). Trujillo del Perú. Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional.

Quilter, J. (Ed.). (2020). Magdalena de Cao. An Early Colonial Town on the North Coast of Peru (Vol. 87). Peabody Museum Press.

Reyes, M., Gómez-Sánchez, I., & Espinoza, C. (2017). Tablas peruanas de composición de alimentos. Ministerio de Salud, Instituto Nacional de Salud.

Vásquez, V., & Rosales, T. (2006). Análisis de Restos Orgánicos (Zoológicos y Botánicos) de CA-35 y CA-17, Zona Urbana Moche—Huaca de la Luna. En S. Uceda & R. Morales (Eds.), Proyecto Arqueológico Huaca de la Luna. Informe Técnico 2005 (pp. 275-302). Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Students , outstanding news